Religion in a WEIRD world

Comparing Northern Ireland to the United States is an often-amusing and sometimes-insightful pastime of mine.

The two countries have an awful lot of differences, population size and diversity being the among most obvious. But both are, of course, western, industrialised, rich, and democratic – WEIRD – like many other countries. (Northern Ireland is not a paradigm of democracy, but let's suspend our disbelief temporarily.)

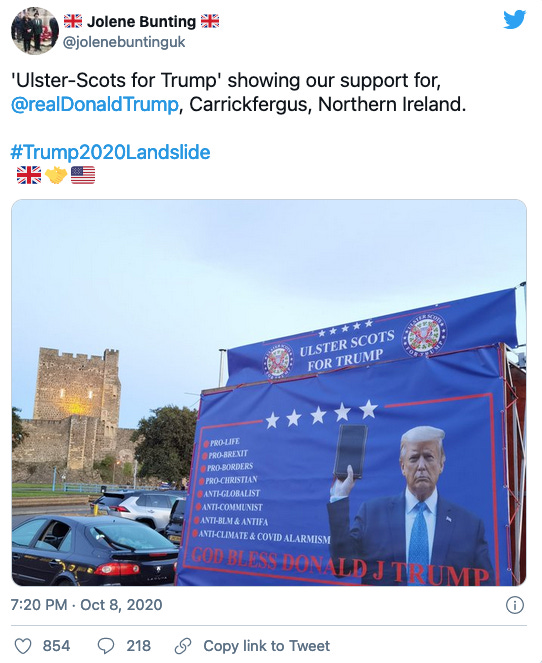

There is also, however, a shared ethnic heritage: the 'Scots-Irish' group in Albion's Seed were English- and Scottish-descended Protestants from modern Northern Ireland. The cultural links between modern Ulster Protestants and American 'borderers' continue today, amplified by the internet:

Northern Ireland's other main ethnic group are Irish Catholics, who can reasonably identify with all the 'Irish-American' narratives and politicians, most famously JFK – and now President Joe Biden. (I am not from this community in Northern Ireland, but in the Republic of Ireland there is certainly a lot of buy-in…)

[N.B. yes, Irish and Catholic and are not synonymous, just as British and Protestant are not. But by and large they're reasonable to lump together, at least for the 20th and early 21st century.]

Political polarisation is another similarity – but it seems that trend might continue longer in NI than it has in the US. It's religion, though, that I want to focus on in this post.

The 'secularisation thesis' holds that as a country modernises, it becomes less religious. The evidence for the thesis was Europe's colelctive abandonment of religion (Christianity) as it modernised.

Has this happened in Northern Ireland? I made a graph of the absolute number of adherents since 1861:

It's mainly the grey and pink parts of the graph that we're interested in (the non-religious). It's clear that there's been an increase, but absolute numbers don't show change in the share of population over time. Let's plot the figures as a share of the total instead:

[There's a small gap in the total for 1971, which I'm not sure how to account for. Some kind of discrepancy between the total population and the number giving their religion which it didn't feel worthwhile to resolve as it's only a small gap.]

The picture now becomes clearer. The established denominations of the 19th and 20th centuries, i.e. Catholicism, Presbyterianism, and the Church of Ireland, have seen their collective dominance weakened in recent years. Closer inspection reveals that this decline has mainly occured among the Presbyterians and Church of Ireland, as Catholicism's share is actually back to where it was in 1861, at around 40%. (Protestants seem to lose more people as they move to adulthood, and they also face a bigger draw to mainland Britain for work and study. Catholic birthrates may be higher too.)

1971 and 1981 show an increase in the 'not stated' group that then declines – why? This was the height of the Troubles, a period of political violence in Northern Ireland, in which people's politics were closely correlated to their religion. Perhaps some people (the graph suggests it might have been Catholics in particular) felt it was not safe to record their religion in a census in those years, and by 1991 the 'not stated' and 'none' groups had reverted to a lower number.

How does this compare to the supposed exception to the secularisation thesis, the United States? The below chart just covers the post-war period, and goes all the way up to 2020, so don't compare it exactly to the NI chart:

The US, then, is increasingly not a Christian country – although, as in Northern Ireland, your experience can vary depending on where you are. I like to think that there's a lot of similarity between, say, Ballymena and the American Bible Belt, just as there is between the relatively cosmopolitan parts of Belfast and some coastal American cities (up to a point).

Based on a roughly similar share of unaffiliated/unanswering people, at around 20% in 2010, both countries are steadily secularising. And that's without considering whether those identifying as Christian are going to church as much as they were before. The 2021 census in Northern Ireland will make the picture clearer, when it's released.

What should we make of this? Neither country is, on this evidence, an exception to the secularisation thesis. But it remains to see how far each one will go down this route.

Catholicism in both countries seems to be surviving, at least in terms of census identification, despite the Pope maintaining the church's conservative stance on the hot-button issues of the day. Protestantism in the US is more diverse in its theology, but the Presbyterian Church Ireland (PCI) has recently become more conservative in its official stances. Most of their congregations are in Northern Ireland, and the church used to be fairly liberal, at least at a denominational level. Some high profile – by Northern Irish standards – individuals have left PCI amidst this new conservative shift, and it's not clear whether this will accelerate the denomination's decline in membership. One academic has calculated the denomination is losing 3,900 members a year. This is, of course, a separate question from whether such stances were the right ones to take.

It's also worth taking into account the effect of the Troubles in the latter half of the 20th century. If someone kills a member of your religious-political tribe, that will cement your identity for years to come. (There was also a strong cultural memory of violence and persecution on both sides that could be tapped into.) I suspect this violence, and the underlying history of conflict, helped to preserve Northern Ireland's strong religious identification for longer than it otherwise would have.

A wider perspective is necessary to speculate about the future: in 2021, religious trends must be discussed in international terms as well as national ones. If you speak English and use the internet, you are almost unavoidably part of an American-dominated cultural conversation, from TikTok to Twitter.

The internet, in this context, has primarily promoted secularisation, as Marc Andreessen recently discussed in his (rather explicit) interview with Niccolo Soldo. Hollywood/Netflix and the biggest American creators on platforms like YouTube and TikTok, typically do not promote religion. The internet religion wars of the 2000s might be over, but content creation defaults to the lowest common denominator, which is non-religious.

But as the rest of the world increasingly comes online and more people identify the cultural importance of the internet, niches are discovered – or created. Opportunity beckons for intellectual entrepreneurs. This might be a writer who realises that there is demand for a religious view of the world. Or an evangelist who realises that one of the best and perhaps most efficient ways to reach the unreached in the West is via the internet.

There are many possible platforms for these entrepreneurs, from Substack to YouTube. And there are many angles they could take, whether critiques of the modern dating market or globalisation-friendly governments. The problems of modernity can serve as the foil for a newly counter-cultural religious movement.

There exists an oppotunity for a religious resurgence, then, or for some kind of successor ideology to take its place. I don't know what's going to happen. But if something changes, it has the opportunity to sweep the world faster than ever before, via the internet.

It's hard to imagine one ideology taking over completely, however. Jordan Peterson is popular, but he has a ceiling. Ditto the likes of Ibram Kendi. Perhaps the future will even out, so that everywhere in the West has some number of Protestants, Catholics, Muslims, and atheists. Co-religionists across the West can use the internet to collaborate with each other and enjoy some of the benefits of centralisation, whilst struggling to achieve dominance in any single locale. Christians can read the Gospel Coalition or Ross Douthat, and atheists can read LessWrong and Scott Alexander. It's the same in other areas – if you care about economics, Marginal Revolution is a good read, no matter where you live.

As the young, English-speaking populations of Africa and Asia come online, I expect there to be new religious and ideological products. Could Western astrology and witchcraft fans find common interests with forms of animism? Does the developing world offer a suitable ideological complement for wellness culture? Could Africans lead a broader Christian revival in the West?

Alternatively, the internet's influence could have its own ceiling, and people will just identify as most others do around them, with a gradual increase in atheism in the coming years. Much of what I've said here is pure speculation, but in a decade's time we'll have more data to examine.

If you want me to write more things like this, you should subscribe to my weekly email, which includes links to what I write and a few extra interesting things.

Comments welcome below.